The Namib Desert ecosystem holds a unique place in Africa’s natural heritage. It is the oldest desert on the continent and one of the most extreme environments on Earth.

Despite its harsh conditions, life in the Namib Desert continues to adapt in remarkable ways. Readers will explore its geography, climate, plant life, animal adaptations, and the ways humans interact with this ecosystem.

The story of the Namib reveals what resilience looks like in the heart of southern Africa. Geological studies indicate that the Namib has existed for over 55 million years, shaped over time by relentless wind, salt-laden fog, and intense solar radiation that define its character.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhere the Namib Begins

The Namib Desert stretches along the Atlantic coast of Namibia for more than 2,000 kilometers. It runs from the Olifants River in South Africa to southern Angola.

Coastal fog often dominates the weather, with less than 10 millimeters of annual rainfall in some regions. Inland areas receive slightly more, but water remains scarce.

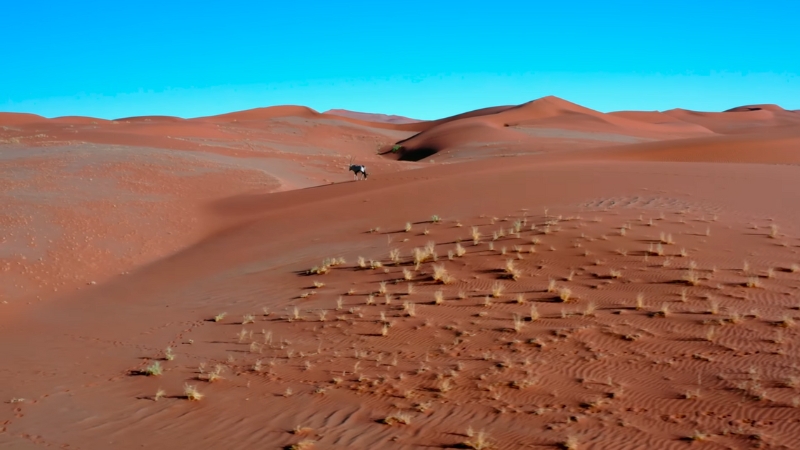

Despite limited moisture, the Namib Desert ecosystem supports life through fog and underground moisture sources. Towering dunes, shaped by centuries of wind, cast long shadows across salt pans and fossilized riverbeds, which hold clues to ancient climates and shifting tectonic plates.

Harsh Yet Predictable Climate

The Namib Desert climate ranks among the driest in the world. Daytime temperatures can exceed 45 degrees Celsius. Nights drop quickly, reaching near freezing in some areas.

Coastal fog forms when the cold Benguela Current collides with warm desert air. This fog provides moisture for many desert plants and animals.

Seasonal temperature patterns remain consistent, with hot, inland air drawing moist fog across the desert floor, offering a steady yet fragile rhythm that defines survival here. Sandstorms, sometimes lasting for hours, can change the shape of entire dune fields in a single day.

Namib Desert Biodiversity

The Namib Desert holds an exceptional level of biodiversity. It supports over 3,500 documented species, with more than 1,000 endemic to the region.

Insects, reptiles, birds, and small mammals dominate the landscape. Namib biodiversity depends on adaptation to heat, limited water, and sparse vegetation.

Some species never drink water directly, relying entirely on fog or moisture in their food. Soil-dwelling bacteria and fungi, although often unseen, play a crucial role in recycling nutrients, breaking down organic matter, and supporting fragile desert roots during brief periods of rain.

Plants That Do Not Need Rain

Namib Desert plants survive without rainfall for years. Welwitschia mirabilis is a living fossil found only in the Namib. It draws moisture from fog and dew through broad leaves. Lithops, or stone plants, blend with the gravel to avoid predators.

Other succulents store water inside fleshy leaves and root systems. Some plant species synchronize seed release with rare rainfall events, germinating rapidly and flowering within days to complete their life cycle before conditions turn hostile again.

Notable Namib Desert Plants

Plant Name

Adaptation Type

Habitat Location

Welwitschia

Fog absorption

Central Namib Basin

Lithops

Camouflage

Gravel plains

Hoodia

Water storage

Inland rocky slopes

Nara melon

Deep root system

Tsondab River areas

Desert Survival Tactics

Animals in the Namib Desert employ specific strategies to mitigate heat stress and conserve water. The fog-basking beetle climbs dunes to collect condensation on its back. Sidewinder snakes move sideways to reduce contact with hot sand.

Golden moles live underground, where temperatures remain stable. Lizards regulate their body temperature by adjusting their body angles relative to the sunlight.

Many species restrict their movements to early morning or late night, timing their activity with temperature drops and dew formation, which are often their only water sources.

Desert Animals and Their Adaptations

Animal

Survival Trait

Daily Behavior

Fog-basking beetle

Fog harvesting

Morning dune ascent

Namib sidewinder snake

Heat avoidance

Nocturnal activity

Golden mole

Subsurface living

Burrows during daylight

Namaqua chameleon

Skin color regulation

Sun-seeking then shade-hiding

Insects and Reptiles in Focus

Insects and reptiles, particularly those found in the desert, form the core of the Namib Desert ecosystem. Beetles, spiders, and scorpions dominate lower elevations. Reptiles such as skinks and geckos often live among rocks, where temperatures tend to be lower.

Some insects, such as tenebrionid beetles, use unique leg movements to direct fog toward their mouths. Reptiles often prey on these insects, completing a desert food web. Camouflage, rapid reflexes, and heat resistance help both predators and prey survive in terrain that shifts constantly with the wind.

Birds and Mammals in Isolation

Namib birds rely on coastal fish, desert seeds, and opportunistic hunting. The dune lark is one of the few endemic birds. It survives in shifting dunes without access to permanent water.

Mammals include oryx, jackals, and the elusive desert-adapted elephant.

These species migrate in response to seasonal water pockets. Large mammals cover vast distances to access grazing areas, while smaller ones, such as rodents, depend on burrows, shaded rocks, and leftover food fragments to sustain themselves.

Unique Species Only Found Here

Several species are endemic to the Namib Desert environment. The Namib web-footed gecko hunts at night using transparent eyelids.

The shovel-snouted lizard escapes predators by diving into loose sand. The tok-tokkie beetle performs a tapping rhythm to communicate.

Each species illustrates survival through specialized behavior. Even minor physical traits, such as foot pads or reflective skin tones, enable these animals to move across hot terrain, find shelter quickly, and maintain hydration with minimal resources.

Unique Namib Desert Species

Species Name

Unique Feature

Habitat Preference

Namib web-footed gecko

Transparent eyelids

Coastal gravel plains

Shovel-snouted lizard

Sand swimming

Inland dunes

Tok-tokkie beetle

Sound communication

Rocky outcrops

Dune lark

Limited water dependence

Dune ridges

Human Footprint in the Namib

In #Namibia, our project partner @GobabebRSH works with Topnaar community, who were displaced & excluded from access to marine resources & decision-making on the #ocean.

Learn more about Topnaar people’s connection to the ocean from this video at 4:55.

▶️https://t.co/WiQl5Dul1Z https://t.co/ATXHLbKsdS pic.twitter.com/lQrvj8vtGX— One Ocean Hub (@OneOceanHub) October 17, 2022

Life in the Namib Desert also includes small human communities. The Topnaar people have lived near the Kuiseb River for centuries. They harvest nara melons, which grow only in dry riverbeds. Tourism and mining shape modern activity in the desert.

Park rangers monitor wildlife, erosion, and illegal poaching. Seasonal festivals, traditional food preparation, and oral storytelling remain integral to daily life, keeping Indigenous knowledge closely tied to the ecosystem that sustains them.

In some areas, handmade boats, clay tools, and carved wooden bowls still serve daily use, preserving heritage in both function and form. Community elders teach desert navigation skills to younger generations, passing down survival knowledge that has no written form but remains accurate over centuries.

Conservation and Climate Pressure

The Namib Desert faces rising threats due to mining, tourism, and climate change. Desert plants and animals are slow to react to environmental stress. Small shifts in rainfall or fog patterns may disrupt the balance.

Protected areas, such as Namib-Naukluft Park, offer hope for long-term conservation. Local guides and scientists monitor species and collect environmental data.

Researchers also rely on satellite imagery, drone surveillance, and automated weather stations to detect ecosystem changes before they become irreversible. Conservation programs are increasingly involving local communities, engaging them in wildlife tracking, eco-education, and visitor management.

Some areas now use motion sensors to track animal movement, and data helps predict which corridors need extra protection.

Local Stories from the Namib

A young guide named Kahuure, raised near the Skeleton Coast, once followed elephant tracks for three days to assist researchers in locating a wandering herd. His memory of landmarks, cloud shadows, and wind direction proved more accurate than any map.

Near Swakopmund, a grandmother named Tuana prepares nara melon porridge each morning, just as her mother did before her, using seeds collected from plants that only fruit once a year.

During school holidays, children in Sesriem gather around fire pits, where elders share tales of star movements and beetles that warn of sandstorms before they arrive. Stories remain essential, connecting people not only to each other but to every insect, plant, and dune that makes the desert a living home.

In the village of Gobabeb, schoolteachers often walk several kilometers to reach students scattered across the sand. Some lessons include how to recognize animal prints, track time by the shape of shadows, or use dried plants to treat fevers.

Locals recall how goats once strayed too far from grazing zones and were guided home by children who had memorized the smell and direction of the wind.

A healer named Naemi carries a bundle of dried herbs for every journey, believing the desert always provides, but only for those who move with care. These moments, simple yet precise, continue to shape daily life in ways no book or satellite can measure.

What Tourists See in the Namib

For visitors, the Namib offers more than just scenery—it delivers an experience shaped by contrast, silence, and scale. On my first visit, I stood at the base of Dune 45 and felt the sand run through my fingers like time itself.

The wind hummed softly, and for a moment, everything else in the world seemed far away. As the sun climbed, light painted the ridges gold, then red, then deep amber, changing the landscape minute by minute.

Some travelers I met shared stories of waking at 4 a.m. just to hike under stars and reach the top before sunrise. One woman from Cape Town wept quietly as fog curled around Deadvlei, telling me it reminded her of home in winter, only more still.

A group of German tourists I joined for a guided walk was silent by the end, not from fatigue, but from awe. Local guides paused often to show tiny prints in the sand, tell stories of disappearing rivers, or let us taste saltbush leaves that survive where nothing else dares to grow.

Evenings were equally unforgettable. One night, we sat near a cooking fire under an open sky, eating oryx meat grilled slowly beside millet cakes sweetened with nara pulp. We listened as a guide named Paulus told stories of beetles that drink fog and birds that never need to land.

Later, lying back on a canvas mat, I looked up at stars so bright they felt almost close enough to touch. No camera could ever explain the quiet power of that moment.

What the Desert Teaches

The Namib Desert ecosystem provides lessons in patience and adaptation. Every living organism in this environment uses energy wisely. There is no waste in the natural rhythm of the Namib.

For scientists, it offers a living laboratory for evolutionary biology. For visitors, it creates a memory of quiet survival under open skies. Many who come here leave with a more profound respect for simplicity, silence, and the wisdom that comes from living with very little.

The quiet expanses and sharp contrasts between dune and sky reveal a world where everything has purpose, yet nothing hurries. Children raised near the desert often describe the dunes as familiar giants, and older generations speak of their silence as a guide when words fall short.

Key Namib Desert Facts (2025)

Metric

Value

Age of the Desert

Over 55 million years

Annual rainfall (coastal)

Less than 10 mm

Endemic species

Over 1,000

Size

About 81,000 square km

Protected areas

Namib-Naukluft, Sperrgebiet

FAQ

Related Posts:

- 10 Oldest Trees in the World You Must Know About in 2025

- What Makes the Fennec Fox So Perfectly Adapted for…

- Mediterranean Monk Seal - Endangered Marine Treasure…

- 6 Unique Plants Found in the Sahara Desert - Rare…

- How Are Camel Eyelashes Unique Among Desert Animals?

- Top 10 Most Dangerous Desert Animals You Should Avoid