The Rub’ al Khali, also known as the Empty Quarter, is the largest continuous sand desert on Earth, spanning over 650,000 km² across Saudi Arabia, Oman, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen.

It receives less than 30 mm of rainfall annually, with summer temperatures often exceeding 50°C (122°F). Despite these hostile conditions, the desert supports a network of adapted wildlife species, each with unique physiological and behavioral traits that allow them to survive where few organisms can.

Table of Contents

ToggleMammals of the Rub’ al Khali

| Species | Key Adaptations | Conservation Notes |

| Arabian Oryx (Oryx leucoryx) | Reflective white coat, slow metabolic rate, survives without direct water | Reintroduced after extinction; IUCN: Vulnerable |

| Arabian Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes arabica) | Large ears dissipate heat, nocturnal, burrows during the day | Stable population |

| Sand Cat (Felis margarita) | Fur-covered feet protect against hot sand, a stealth hunter | Rarely seen; classified as Near Threatened |

| Arabian Wolf (Canis lupus arabs) | Small, thin frame for desert mobility; survives in isolation | Declining numbers, listed as endangered in the Arabian Peninsula |

The Arabian red fox is lean and opportunistic, eating everything from beetles to small birds. The sand cat, one of the most elusive desert predators, is perfectly adapted to hunt silently across scorching dunes. The Arabian wolf, though fewer in number, manages to thrive through a solitary, scavenger lifestyle that minimizes energy use in a harsh ecosystem.

Reptiles That Dominate the Sand

| Species | Behavior | Adaptation Summary |

| Horned Viper (Cerastes gasperettii) | Ambush predator moves by sidewinding to avoid overheating | Camouflage, venomous, heat-sensitive |

| Spiny-tailed Lizard (Dhub) (Uromastyx aegyptia) | Burrower, basking reptile, vegetarian diet | Stores fat in tail, hibernates in extreme conditions |

| Fringe-toed Lizard (Acanthodactylus spp.) | Sand surfer, fast mover, insectivore | Fringed toes prevent sinking, burrows to cool |

| Geckos (various species) | Night active, hunts insects | Adhesive toe pads, high humidity tolerance in microhabitats |

The dhub is a heavy-bodied lizard that hibernates during the hottest months, eating hardy desert shrubs when active. Fringe-toed lizards run across soft dunes with ease, using their speed to escape predators and to feed quickly during cooler hours.

Desert geckos prefer rocky crevices and gravel plains, avoiding open dunes and making the most of whatever insect life they can find.

Birds That Brave the Barren Sky

| Species | Ecological Role | Adaptations |

| Desert Lark (Ammomanes deserti) | Insect control, seed dispersal | Blends with surroundings, low-energy flight |

| Cream-colored Courser (Cursorius cursor) | Predator of beetles and ants | Fast runner, nests in open areas |

| Brown-necked Raven (Corvus ruficollis) | Scavenger and opportunistic feeder | Smart forager, withstands extreme temperatures |

| Eagle Owl (Bubo bubo ascalaphus) | Nocturnal predator | Silent flight, sharp vision, high rodent consumption |

The desert lark is one of the most commonly sighted birds, perfectly blending with its sandy backdrop and using soft calls and small movements to avoid predators. The cream-colored courser sprints across open plains in search of insects and lays eggs directly on the sand, relying on camouflage.

The brown-necked raven, one of the few intelligent scavengers in the region, feeds on carcasses and even leftover human waste. The eagle owl, a top-tier nocturnal predator, silently glides over dunes, hunting rodents and reptiles with acute night vision.

Invertebrates: Masters of Microclimates

| Species | Role in Ecosystem | Survival Strategies |

| Desert Dung Beetle (Scarabaeus spp.) | Decomposer | Rolls dung into burrows; survives with minimal water |

| Scorpions (Leiurus quinquestriatus, others) | Predator of insects | Stores venom, avoids heat, hides by day |

| Camel Spider (Solifugae) | Mid-tier predator | Fast runner, voracious hunter |

| Ants & Termites | Soil engineers | Deep nests regulate humidity and temperature |

Scorpions, especially the yellow fat-tailed scorpion (Leiurus), are slow, methodical hunters that rely on venom and stealth, often emerging only for minutes at night.

The camel spider, though not venomous, is a highly aggressive predator of insects and small reptiles. Ants and termites build elaborate subsurface colonies, creating microclimates that allow for temperature stability and complex social behavior.

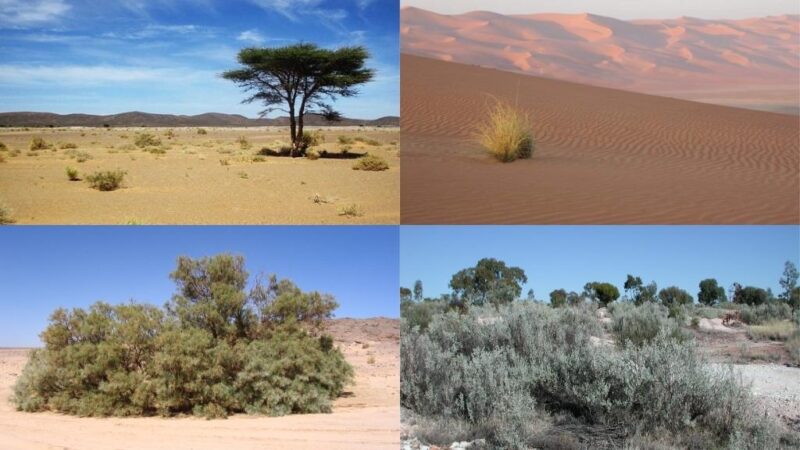

Rare Flora as a Support System

| Plant Type | Function | Adaptation |

| Acacia Trees | Shade, nitrogen fixation | Deep roots, small waxy leaves |

| Saltbush (Atriplex spp.) | Soil stabilizer, herbivore food | Salt tolerance, water retention in leaves |

| Ephemeral Grasses | Seasonal forage for herbivores | Fast germination after rainfall |

| Desert Shrubs | Habitat for insects, birds | Low profile, drought-resistant physiology |

They also improve soil fertility through nitrogen fixation. Saltbush thrives in saline soils and provides much-needed vegetation for grazing animals like the oryx.

After rare rains, ephemeral grasses rapidly grow and die within weeks, enabling fast feeding and breeding cycles for insects and rodents. Desert shrubs, such as Zygophyllum, provide cover for invertebrates and nesting spots for small birds.

Exploration of these isolated plant zones requires careful access planning. For researchers and travelers navigating sandy terrain to study desert flora and fauna firsthand, Renty offers a fleet of vehicles equipped for desert travel, including 4x4s ideal for crossing soft dunes and reaching remote areas without harming sensitive habitats.

Properly equipped vehicles are essential for accessing remote areas of the desert without causing harm to fragile habitats. These vehicles not only provide the necessary mobility to reach places where few can go, but also help minimize the environmental impact by allowing people to move across the desert’s harsh landscape with greater efficiency. Whether studying wildlife or conducting conservation efforts, having the right transport is indispensable in navigating the Rub’ al Khali’s vast and unforgiving environment.

Survival Mechanisms Across Species

| Mechanism | Description | Animal Examples |

| Nocturnality | Avoiding daytime heat by being active at night | Sand cat, scorpion, fox |

| Water Efficiency | Drawing water from food or conserving it internally | Oryx, dhub, beetles |

| Burrowing | Creating cooler, humid shelters underground | Lizards, wolves, and insects |

| Camouflage | Avoiding detection through color blending | Horned viper, desert lark |

| Behavioral Thermoregulation | Timing activity to thermal windows | Geckos, fringe-toed lizards |

Burrowing behavior allows species to maintain safe body temperatures, and camouflage ensures both predators and prey can operate without drawing attention. Timing activity during the early morning or late evening hours is another shared trait – one that is often the difference between life and death.

Protected Areas and Conservation Efforts

Uruq Bani Ma’arid Reserve Overview

| Factor | Description |

| Size | ~12,000 km² |

| Location | Western edge of Rubal Khali, Saudi Arabia |

| Species Protected | Oryx, sand gazelle, foxes, wolves, reptiles |

| Management | Saudi National Center for Wildlife |

| Focus Areas | Rewilding, habitat preservation, and anti-poaching patrols |

Conservation efforts in the Rub’ al Khali focus on habitat protection, species reintroduction, and limiting human encroachment.

The Uruq Bani Ma’arid Reserve is one of the largest protected zones in Arabia, home to some of the region’s most endangered species. It is part of a wider regional effort that includes GPS tracking of oryx, predator control, and educational outreach to surrounding communities.

Food Web Snapshot

| Level | Examples |

| Primary Producers | Saltbush, ephemeral grasses |

| Primary Consumers | Dhub, oryx, insects |

| Secondary Consumers | Sand cat, Arabian fox, fringe-toed lizard |

| Tertiary Consumers | Eagle owl, horned viper, Arabian wolf |

| Decomposers | Dung beetles, termites, fungi (limited) |

At the top, animals like Arabian wolves and large owls dominate. Nutrient recycling is slow, but beetles and termites maintain basic ecological balance.

Conclusion

Though it seems lifeless at first glance, the Rub’ al Khali hosts a specialized, self-sustaining ecosystem. Species here are engineered for extremes, relying on centuries of evolution to survive on minimal resources.

As climate pressures grow, these survivors of the Empty Quarter may hold clues for adapting to a warming planet. Protecting their habitat is not just about preserving beauty – it’s about safeguarding evolutionary ingenuity.

Related Posts:

- How the Addax Antelope Survives the World’s Harshest Desert

- Where To See Wildlife Without the Crowds in Europe

- Life in the Namib Desert - Africa's Oldest Desert…

- How Are Camel Eyelashes Unique Among Desert Animals?

- Top 10 Most Dangerous Desert Animals You Should Avoid

- What Makes the Fennec Fox So Perfectly Adapted for…